Are you related to any convicts? There was a time when having convict origins was something people didn’t talk about, but the more distance there is between the current generation and the convicts, the more acceptable it has become.

Perhaps it’s also that it’s estimated at least 20% of Australians have convict ancestry. Added to which, some of the crimes which resulted in transportation in the 18th and 19th centuries were relatively minor when considered in today’s context. When you dig into the circumstances, there’s also often a lot more to the prisoner’s defence than meets the eye, and very little compassion on the part of the governing authorities.

Having a convict in the family can certainly provide some interesting documentary evidence, and through my research I’ve discovered no less than ten convicts in my family. They include some of my 3x, 4x, 5x, and 6x great-grandparents, and appear on my maternal and paternal lines. These ancestors come from diverse backgrounds and places, and were transported to New South Wales for a variety of crimes between 1793 and 1836.

Patrick Humphreys (or Humphries/Humphryes) was the earliest of these convict arrivals. He was from Dublin, convicted of stealing sheet lead, and transported on the Boddingtons in 1793.

Margaret Boyle was also Irish-born, a married woman with two children who was charged with uttering forged notes (using forged money, but not actually making the forgeries). She was tried at Lancaster in 1823. Her death sentence was commuted to life transportation and she arrived aboard the Brothers (I).

Eighteen-year-old George Dowling was a warehouse assistant sentenced to seven years for stealing stockings and fabric. Despite petitions from his parents and a letter from the Duke of Clarence, the future King William IV, George was transported on the Royal Admiral, arriving in 1800. He married Mary Ann Reynolds, the daughter of another convict.

Edward Reynolds was married with six children when he arrived on the Atlantic in 1800, convicted of stealing cows. It wasn’t the first time he’d been charged with this offence, having been acquitted less than six months earlier. His wife Sarah and some of their children, including Mary Ann, followed him as free settlers five years later, but Sarah eventually returned to England.

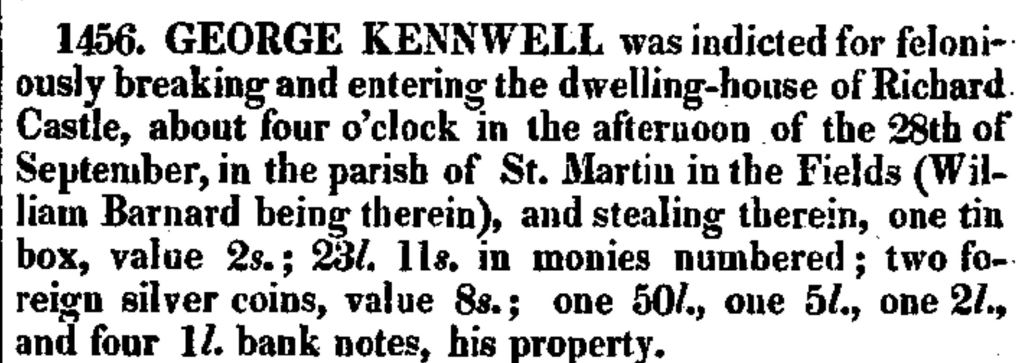

A native of Nottingham, George Kennewell (or Kenniwell) was charged with breaking and entering the house of his London employer, and stealing a tin filled with money. Found guilty of theft, but not breaking and entering, he was transported on the Isabella in 1818.

Harriet Sleigh (or Slea) nee Sampson travelled on the Maria (I) with her young son, and arrived the same week as her future husband, George Kenniwell. She had been found guilty of stealing cloth and was sentenced to death, which was commuted to life transportation.

Mary Ann Rankin was a native of Scotland, working in Hull in 1829 when she was charged with stealing clothes. Whether or not it was true, Mary was described at the time as “although young in years … a proficient in crime”. She was transported on the Sovereign.

Richard Pickering was one of three brothers from Yorkshire convicted of housebreaking and sentenced to death. Given a reprieve, they arrived in New South Wales on the Prince Regent in 1827. A fourth brother was transported for a different offence in 1830.

William Vaughan was from Worcestershire where he was charged and found guilty of highway robbery when he stole a watch and some money. He arrived on the Fairlie in 1833 at the age of 21.

The last of my convict ancestors to arrive was Thomas Hodge. He was a blacksmith from Bath who was convicted of housebreaking and transported aboard the Lady Kennaway in 1836.

There are some fascinating back stories, twists, and turns in the lives of these convict ancestors. Stay tuned to learn more about them in future posts.

Selected references

Digital Panopticon, ‘Convicts and the Colonisation of Australia, 1788-1868’, https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/Convicts_and_the_Colonisation_of_Australia,_1788-1868, accessed 2 January 2024.

Traces, ‘Researching your convict ancestry’, https://tracesmagazine.com.au/2019/07/researching-your-convict-ancestry/, accessed 2 January 2024.

Industry & Perseverance: A History of David Brown (1750-1836) and Family, http://www.davidbrown1801nsw.info/, accessed 19 February 2022.

‘Forged Holywell Notes’, Lancaster Gazette, 12 April 1823, p. 4, FindMyPast.co.uk, accessed 26 February 2016.

Margaret Boyle, Brothers (I), 1823, Correspondence and Warrants, The National Archives, Kew, Surrey, England, HO13, England & Wales, Crime, Prisons & Punishment, 1770-1935, FindMyPast.co.uk, accessed 31 January 2021.

Dowling, George, Royal Admiral, 1799, Correspondence and Warrants, The National Archives, Kew, Surrey, England, HO13, England & Wales, Crime, Prisons & Punishment, 1770-1935, FindMyPast.co.uk, accessed 3 January 2024.

Dowling, George, Royal Admiral, 1799, Judges’ Reports On Criminals 1784-1830, The National Archives, Kew, Surrey, England, HO47, England & Wales, Crime, Prisons & Punishment, 1770-1935, FindMyPast.co.uk, accessed 3 January 2024.

Trial of George Kennwell, 29 October 1817, Old Bailey Proceedings Online (t18171029-24), accessed 3 January 2024.

Trial of Harriett Slea, 15 January 1817, Old Bailey Proceedings Online (t18170115-25), accessed 3 January 2024.

‘Friday – Second Day.’, Hull Packet, 20 January 1829, p. 2, FindMyPast.co.uk, accessed 26 December 2017.

‘Yorkshire Assizes. Monday, March 26.’, Sheffield Independent, 31 March 1827, p. 2, FindMyPast.co.uk, accessed 15 August 2021.

‘Worcester Summer Assizes’, Worcester Journal, 25 July 1833, p. 4, FindMyPast.co.uk, accessed 3 January 2024.

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 9 July 1835, p. 3, FindMyPast.co.uk, accessed 4 September 2015.

No convicts for me. (Or Irish)

I do think being transported worked out extremely well for many. No chance of being given land in Britain. etc

LikeLike

I agree. Although life was generally pretty difficult in the colony, the prospects had potential and descendants often benefited .

LikeLike

I have a soft spot for the convicts in my ancestry searches. I was always told there was no information on family and it was assumed my grandfather was adopted. WRONG After 2 years of research I have found family I didn’t know I had, hence the “soft spot”-to the family member not the crime. My family crimes are too numerous to list and generationally every generation I can find including my own brother. We have murder, rape, robbery, vagrancy, lewd acts and so on and so forth. I am working on a theory that crime may in fact be genetic. Oh to be young enough to restart a career and have to do a thesis, I’d pick genetic crime and forensic profiling.

Thank you for sharing your story.

Barbara

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m still finding new family members after almost 30 years research. It’s never too late to find, try or start something new 🙂

LikeLike

[…] 21, Matthew 25, and John 29, were charged and convicted of house breaking. Sentenced to death, the brothers were instead transported to New South Wales aboard the Prince Regent in […]

LikeLike

[…] try a different application for AI. Using information from official records I wrote descriptions of my convict ancestors. Then I asked an AI bot to create images of them based on the […]

LikeLike

[…] at length in the newspaper. It’s possibly the longest and most detailed report of one of my convict ancestors. The evidence against Margaret does seem rather damning, even allowing for bias and journalistic […]

LikeLike