One of the most common family secrets you’re likely to find is that of illegitimate births. They might be locked away and unknown, or they may an open secret, one that is known, but generally not talked about or officially acknowledged.

Not a lot is known about the early life of my 4x great-grandmother, Elizabeth Southern, also known as Betty. However, the circumstances of her family and a complex web of DNA matches suggest she was probably born illegitimately. She gave birth to eight illegitimate children herself. Elizabeth lived in the Huyton region, east of Liverpool in Lancashire, throughout the first part of her life, and it’s there her children were brought up.

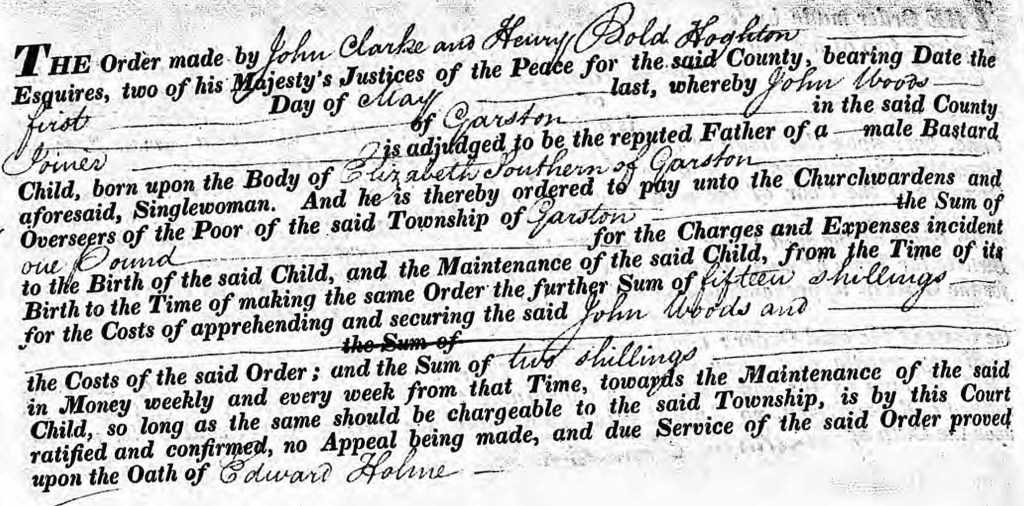

I found some of Elizabeth’s children through the Lancashire Quarter Session Records and Petitions. These records include information about what is known today as child maintenance, but was at the time more commonly called bastardy bonds. I’ve also identified some children and cross-referenced them through other records including later civil registrations and the census.

‘Bastardy papers’

Quarter Session Records and Petitions included the details of people given support by their parish, as part of the Poor Law which made looking after those in need the parish’s responsibility. When an illegitimate child was involved it was in the interests of parish to identify the child’s father and make him pay for the child instead.

The mother would go before the local court and name the father. The father was often also brought before the court, and pressured to marry her. If they didn’t marry, he could be directed to pay either a regular amount or lump sum for the child’s up keep. The money was generally paid to the parish who were expected to use it for that particular child.

The introduction of the New Poor Law in 1834 was intended to reduce the financial impact on the parish further. It meant support was only given if those in need left their homes and went to a workhouse, where they were subject to a raft of harsh circumstances and new difficulties. The New Poor Law, and the introduction of civil registration in 1837, is likely why the Quarter Session Records and Petitions only include details of some of Elizabeth’s children, those born before 1834. There are however clues in official records for those born after 1834.

Sadly, more than a quarter of illegitimate children born in Lancashire in the 1840s died before their first birthday. This was generally put down to poverty and a lack of childcare for single mothers.

Elizabeth emigrates

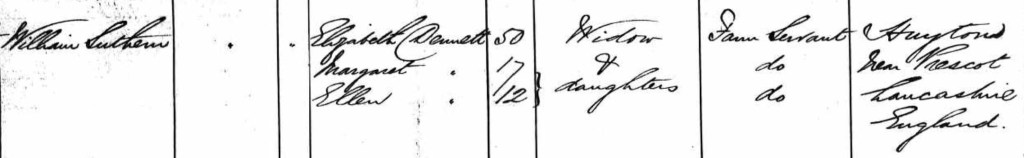

Elizabeth arrived in Australia aboard the Admiral Lyons in December 1858 when she was in her late fifties. With her were her two youngest surviving daughters: my 3x great-grandmother Margaret who was 18, and her sister Ellen who was 15.

Elizabeth, Margaret and Ellen were assisted immigrants sponsored by William Southern, meaning he paid for their journey. William was Elizabeth’s son, and Margaret and Ellen’s half-brother, and he’d arrived in Australia on the Midlothian almost ten years earlier, as a 21-year-old farm servant.

In researching their life before Australia I discovered Elizabeth married John Dennett in October 1843, when she was in her early forties. It’s the only marriage I’ve found for her, and until then she used the surname Southern/Suthern. John Dennett, a farm labourer, is believed to be the father of five of Elizabeth’s children, only one of whom was born after they married. My research discovered Elizabeth had at least four other children born to three different fathers.

I’ve found researching Elizabeth and her children a fascinating though frustrating experience. The information learned from the records makes me even more curious about their lives.

Identifying Elizabeth’s children

Fathers are named in the Quarter Session Records and Petitions for the first four of Elizabeth’s children who were given their mother’s surname Southern.

The next three children were given the middle name Dennett which suggests John Dennett was probably their father, despite him not being specifically named. DNA matches confirm that John actually was the father of Margaret and Ellen, and Ann the eighth child was born legitimately to Elizabeth and John Dennett.

Female Southern born 1822 to reputed father John Hughes in the township of Winwick with Hulme. Although recorded in the Quarter Session Records and Petitions, nothing further has been found about this child. Elizabeth would have been about 21 when she was born.

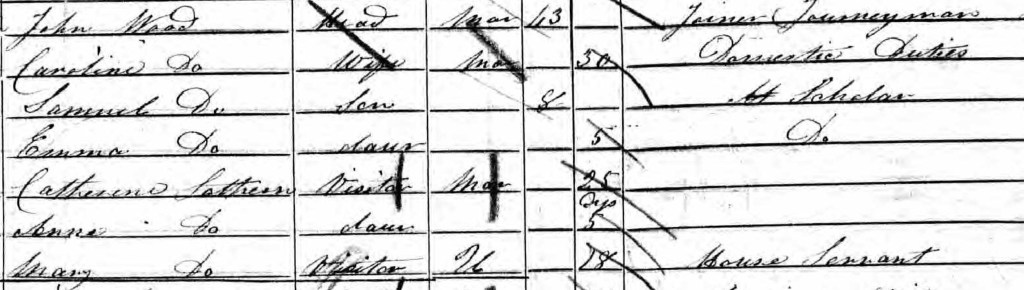

Catherine Woods Southern born 1826 to reputed father John Woods in the township of Garston. Catherine went on to have at least two children of her own, both of whom were born illegitimately: daughter Ann who died of hydrocephalus aged 3 and son William.

William Southern born 1827 to reputed father John Woods in the township of Garston. William emigrated and settled in Australia where he married Helen Thomas nee Bramhall in 1855. He died in 1872 at the age of 45, and was described as a respected resident with a large family and numerous friends.

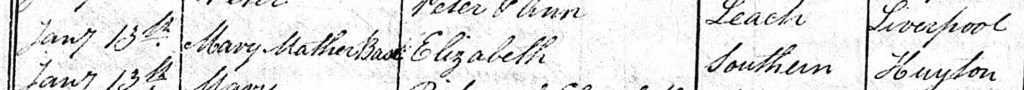

Mary Mather Southern born 1832 to reputed father Robert Mathers in West Derby. Mary married naturalist John Bramhall in 1854.

Peter Dennett Southern born 1837 in Huyton with no father recorded in the civil registration, but given his middle name it’s likely to have been John Dennett. Records of Peter’s marriage list John Dennett as his father.

Margaret Dennett Southern born 1838 to reputed father John Dennett in Huyton. Margaret died of inflammation on the chest at eight months.

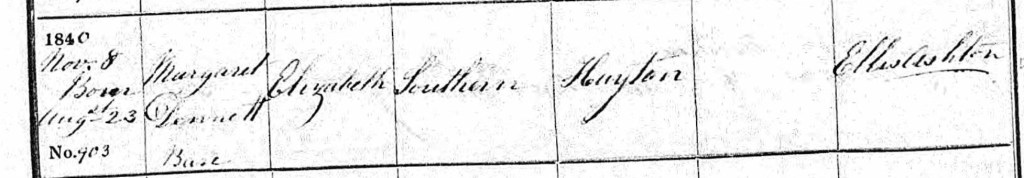

Margaret Southern Dennett born 1840 in Huyton to father John Dennett, and probably named after her deceased sister. In Australia she married Francis Philip Toms with whom she had seven children, and was widowed young. Margaret died in 1917 after a long illness.

Ellen Dennett born 1843 in Huyton to father John Dennett. Ellen was born just months before her parents married. In Australia she married Robert Evans and had many children. She died at the age of 88.

Ann Dennett born 1846 in Huyton to father John Dennett. Ann died of smallpox before her second birthday.

Selected references

FamilySearch, ‘Illegitimacy in England’, https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Illegitimacy_in_England, accessed 22 February 2025.

London Lives, ‘Bastardy Bonds: Securities for the maintenance of bastard children’, https://www.londonlives.org/static/WB.jsp, accessed 22 February 2025.

Norfolk Record Office, ‘Illegitimacy’, https://www.archives.norfolk.gov.uk/article/31121/Illegitimacy, accessed 22 February 2025.

Kim Hunter Genealogy, ‘Illegitimacy and infant mortality in four Lancashire parishes 1840-1849’, http://www.kimhunter.co.uk/2022/09/illegitimacyandinfantmortality.html, accessed 22 February 2025.

GenGuide, ‘Bastardy Bonds & Documents (Parish & Poor Law)’, https://www.genguide.co.uk/source/bastardy-bonds-documents-parish-poor-law/, accessed 22 February 2025.

UK Parliament, ‘Poverty and the poor Law’, https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/livinglearning/19thcentury/overview/poverty/, accessed 22 February 2025.

The National Archives, ‘1834 Poor Law’, https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/1834-poor-law/, accessed 22 February 2025.